Embracing China's economic rise

The world stands to gain from China's growth, despite the alarmist rhetoric

China’s rise in the world economy is arguably the most significant economic and political event of the 21st century. It’s reshaping global trade and geopolitics at astonishing speed. Much of the West, especially the US, has responded with alarm. Donald Trump’s tariffs are the clearest example. But the hostile response to China’s rise is misguided. The rise of China is not a threat to global stability — it’s a development that we should welcome.

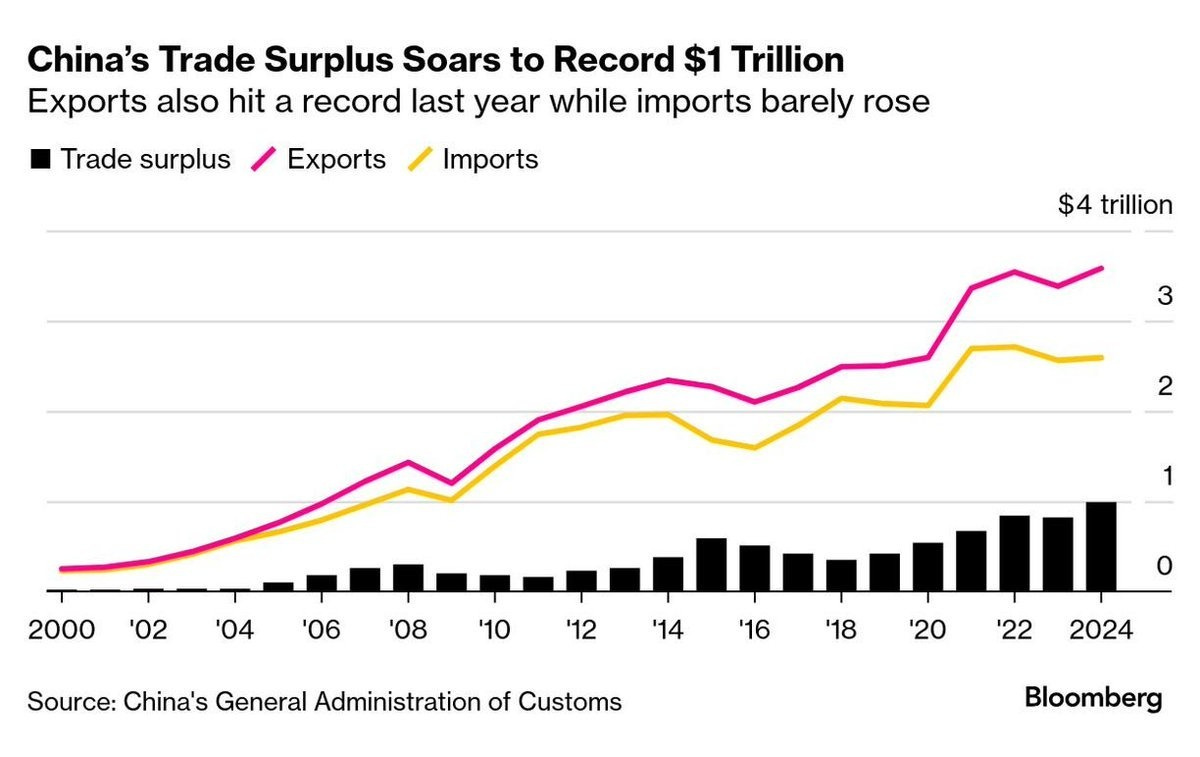

China’s rise to economic superstardom has been rapid and without precedent. The country’s dominance in global trade underpins this rise: China recently became the first country in history to record a trade surplus of $1 trillion.

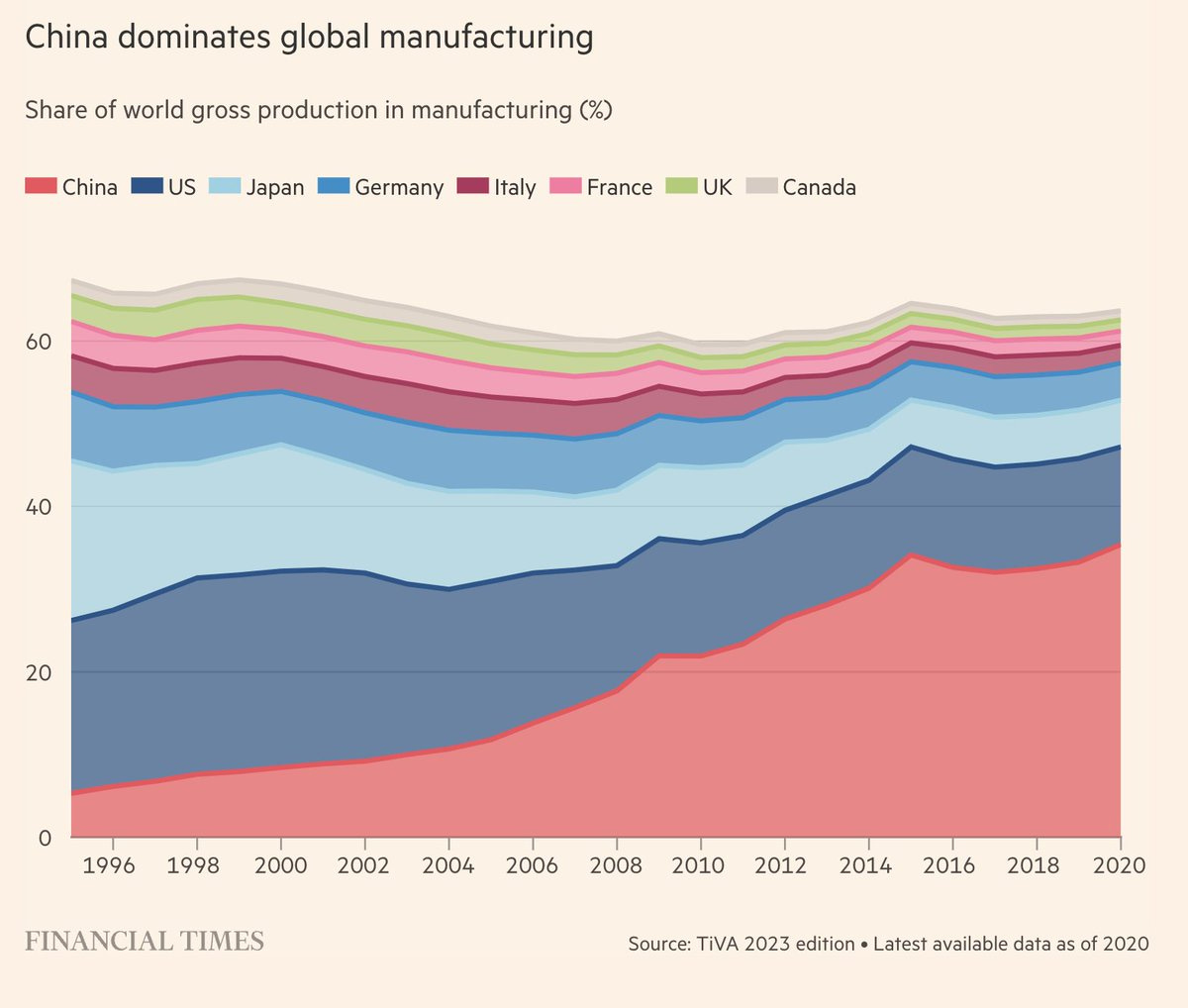

This dominance has been made possible by an export-led industrialisation push. China plays a part in practically all global manufacturing industries. It now accounts for more than 35% of global manufacturing, a number which is expected to increase to 45% by 2030.

China’s dominance in global trade and global manufacturing have raised alarm bells in some countries, particularly the US, which increasingly views China as an economic threat and competitor. The hostile stance towards China has practically reached bipartisan consensus in the US now. Since 2018, both Republican and Democratic administrations have implemented strict trade restrictions aimed at China, such as export restrictions and tariffs.

There are of course legitimate reasons to worry about China’s dominance in global trade and manufacturing. If China’s dominance in these areas keeps growing, there will simply not be enough of the ‘pie’ to share between the rest of the world. Beyond the US, many countries have expressed concerns about their ability to compete with China, including Germany, Japan, South Korea, Chile, Turkey and India, to name a few. However, we should keep in mind that China has not by itself eroded manufacturing capabilities in these countries or prevented manufacturing capabilities in these countries from developing. It’s a complicated picture.

With respect to the ties that China is building abroad, the picture is also complicated. Kyle Chan argues that China has diverse strategies of ‘industrial diplomacy’ abroad. In some countries, such as Brazil, Indonesia, and Mexico, China is ramping up manufacturing investment. But in other countries, most notably India, China is limiting the flow of workers and equipment.

China’s rise in the world economy clearly comes with benefits and drawbacks. But I’d argue that the benefits outweigh the drawbacks.

The West has profited from China’s rise

China started becoming a big player in the global economy in the 1990s and 2000s, marked by membership in the World Trade Organization in 2001. This was welcomed by most countries in the West. For consumers and corporations in the West, China’s integration into the world economy meant access to vastly cheaper manufactured goods and access to a larger variety of manufactured goods, both as inputs and finished goods.

One country in particular took advantage of the efficient and low-cost production systems that China offered: the US. William Milberg and Deborah Winkler have documented that the price of manufactured goods imports into the US have declined massively relative to US consumer prices in non-traded sectors between the 1980s and early 2010s, in some instances by more than 40%.

US corporations are among the greatest beneficiaries of China’s integration into the world economy. There is a common misconception that Chinese firms are outcompeting US firms. While this is true in some sectors — and is increasingly happening —, the capitalist rise of China has actually boosted US structural power in certain ways, especially by generating more profits for US corporations. Research by Sean Starrs finds that most global industries are still dominated by US corporations, aided by China’s rise. Starrs highlights that both investments in China and imports of inputs from China have enabled US corporations to maintain their global dominance.

The electronics giant, Apple, is the perfect case in point. Apple has made a fortune in China: $227 billion in operating profit over the past 10 years, which accounts for over a quarter of its operating profit during this period.

US tech giants’ dependency on Chinese goods was in the spotlight recently. When US president Donald Trump announced steep tariffs on Chinese imports in April 2025, CEOs in the US tech industry were outraged as the share prices of their companies plummeted. But these CEOs rapidly and successfully lobbied Trump to quickly lower tariffs on Chinese-made electronics items, which big tech firms, such as Apple, Nvidia and Microsoft, are completely dependent on. Although many of these corporations have plans to become less dependent on China’s production systems, it’s simply not economically profitable for them at this point. Apple’s supply chain is a good case in point. 157 of the 187 suppliers used by Apple currently have a presence in China.

It’s commonly argued that China has benefitted from the economic relationships forged with US corporations — both through attracting investments and through supplying US corporations with inputs. China has indeed utilised relationships with companies such as Apple in clever ways in order to build up technological capabilities. But we can hardly claim that China has gotten a fair deal. For example, throughout the 2010s, Chinese workers and firms that assembled the iPhone got less than 1.5% of the final retail price. Chinese workers have literally toiled for pennies in factories serving US markets.

China’s rise offers new (and potentially better) partnerships for the Global South

China has made a committed effort to strengthen economic relationships across the world. For countries in the Global South, this is an opportunity to strengthen ties with a superpower that shares a common challenge: trying to emerge from the economic periphery. In this sense, China provides a welcome alternative to existing North-South relationships, which have often been (and often still are) characterised by imperial arrangements designed by the North to extract profits and resources from the South. While China may not be a magic bullet for economic development in the Global South at large — and while we need to recognise China’s diverse strategies in the Global South —, it would not take much for China beat the poor track record of Western involvement in developing countries, especially in Latin America and Africa.

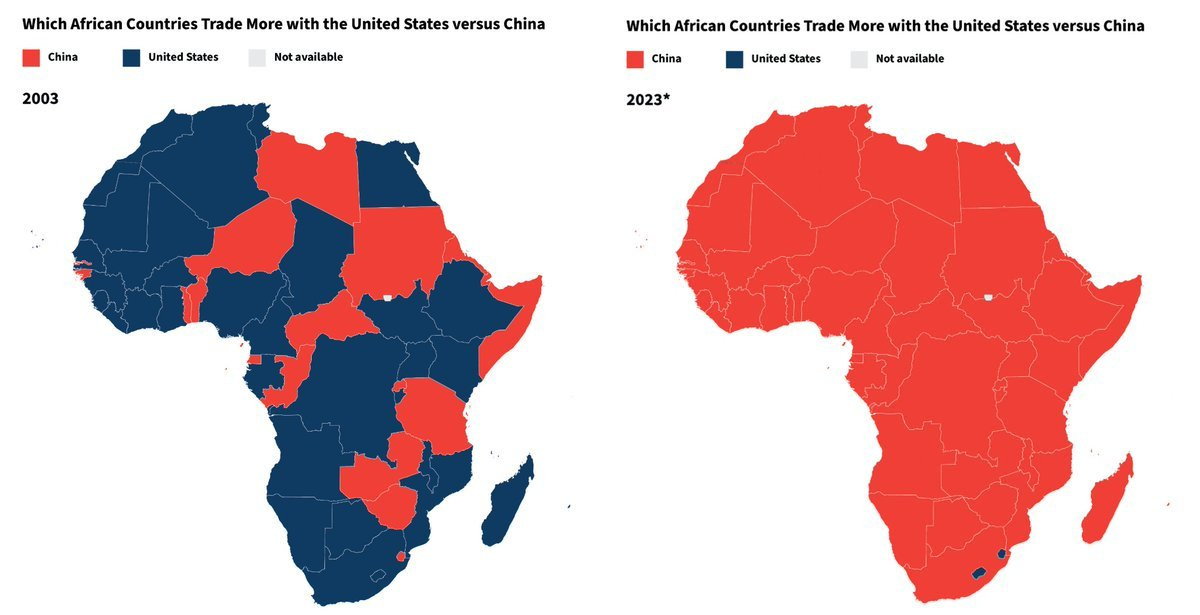

We should pay particular attention to Africa, where China has strengthened both economic and political relationships. By now, China is the most important trading partner for almost all African countries. This stands in stark contrast to the situation in the early 2000s, when African countries traded more with Western partners, such as the US.

China has become highly popular in Africa. In Sub-Saharan Africa, positive views of China outweigh negative views by a factor of about 3 to 1 across nearly 300 surveys in the region. China is also contributing to economic development in Africa. A review of over 100 articles found that Chinese firms in Africa have a positive impact on economic development, capacity building, and innovation.

This does not mean that China’s economic impact in Africa is unambiguously positive. But the pendulum tends to swing too much in the other direction, uncritically reinforcing negative narratives about China's rise in Africa — often with little to no grounding in real evidence. It’s important to debunk such narratives. The narrative about China's "debt-trap diplomacy" in Africa is a good example. This refers to a perceived strategy whereby China provides substantial loans to African nations as a way to trap them into debt. This narrative has turned out to be nonsense. A study that looked at more than 1,000 loans to Africa found that Chinese lenders never seized assets, never used courts to enforce payments, and never applied penalty interest rates.

China is a climate champion

China’s impact on the climate is heavily debated. On the one hand, China’s industrialisation has entailed considerable growth in greenhouse gas emissions. On the other hand, China has become a global leader in efforts to develop technology for renewable energy. I would argue that the benefits of the latter outweigh the costs of the former.

It’s important to look into the details of China’s growing emissions to understand the full context of them. If we look at consumption-based emissions (which is vital because we want to account for where things are consumed, not only produced), China is not nearly as bad as some other major countries, most notably the US, in per capita terms. The below chart, which depicts this, doesn’t even account for countries’ historical emissions. If it did, most countries in the West would score far worse than China. So, while China can surely work on reducing their emissions, the responsibility to do so primarily lies with the West.

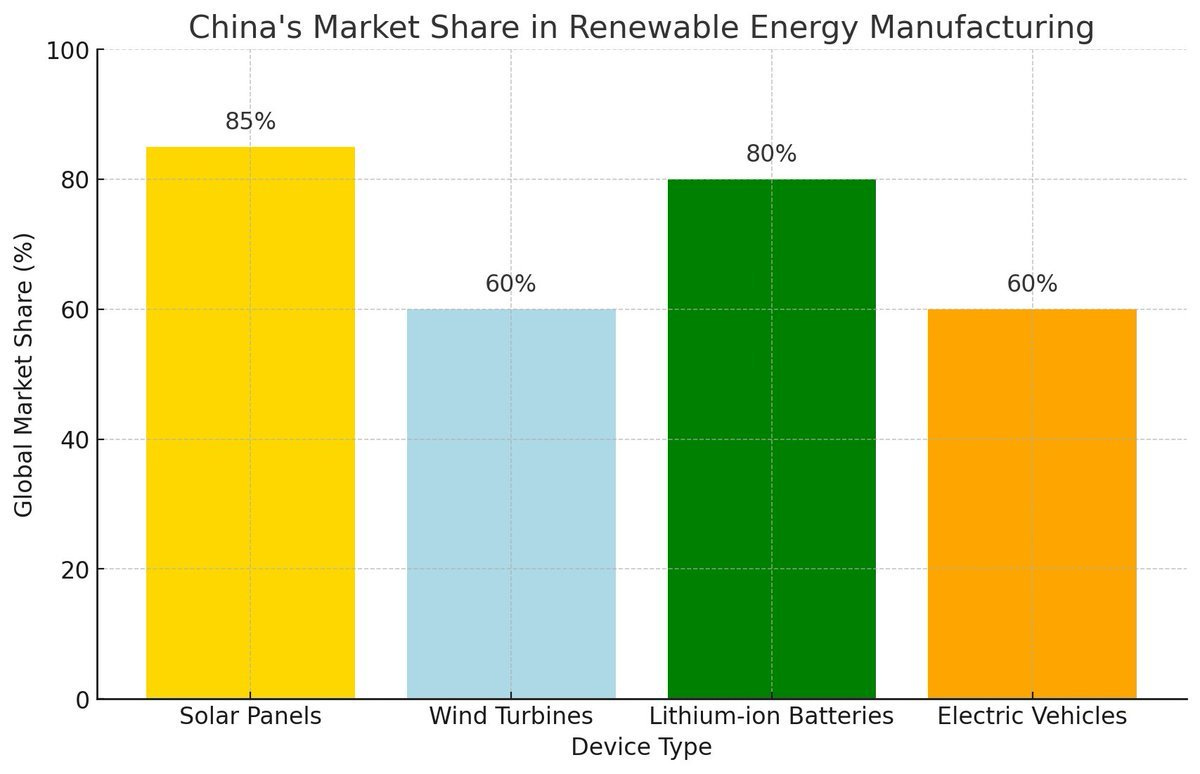

China’s growing emissions can largely be attributed to rapid industrialisation. In this respect, it’s important to note that China has used its industrialisation and increased productive capacity to massively scale up production of renewable energy devices. As of 2024, China accounted for 60-85% of the global market share across a range of renewable energy devices, including the production of solar panels, wind turbines, lithium-ion batteries and electric vehicles. This is not only helping China slow down growth in emissions — it’s also offering other countries to do the same by exporting these products to them.

What’s good for China is good for a big part of the world

I’d like to conclude this post by highlighting a point often overlooked in the debate on China’s rise: if China does something that benefits a majority of their own population, this, by definition, benefits a big part of the world. How? Because China accounts for roughly 17% of the world’s population. According to World Bank data, since 1980, the number of people lifted out of poverty in China exceeds the number of people lifted out of poverty in the rest of the world. This is a remarkable achievement by China, and should be celebrated by anyone who cares about international development.

We see that China’s economic ascent, while not without challenges, has delivered undeniable benefits. The alarmist anti-China rhetoric has unfortunately overshadowed the positive aspects of China’s integration into the world economy. In a world quick to view China’s rise with suspicion, it’s time to shift the narrative.

Superbly written. Much needed reality check. I suspect you held held back rather a lot given space constraints and the audience you're trying to teach. You could do a series of articles....

very nice article! Welcome on Substack