Why developing countries can't skip industrialization

The enduring case for manufacturing-led development

The idea that developing countries can bypass manufacturing and leapfrog straight to services has become more fashionable. Services are becoming a more important source of economic growth and commercial activity, and many question whether traditional industrialization still matters — or is even possible. India’s business process outsourcing boom, UAEs success with financial services, and the Phillippines’s call centre surge are all held up as proof that countries can potentially skip factory-based production.

We should acknowledge new service-based development opportunities. But the notion that countries can skip industrialization is mostly wishful thinking. The evidence shows that very few countries have developed without a strong, competitive manufacturing base. The reason is that services cannot replace what manufacturing uniquely provides: sustained productivity growth, innovation, trade, and the foundation for a strong economy.

The historical record is clear

Virtually every country that has successfully transformed from poor to rich has done so through industrialization. Between 1750 and 1950, the West’s establishment as the world’s economic hegemon was fundamentally a process of becoming the world’s manufacturing hegemon. Since 1950, this pattern has persisted with remarkable consistency. A World Bank study published in 2008 identified 13 countries that sustained annual growth rates of 7% or higher for a period of 25 years or longer. Among these growth miracles, only two — Botswana and Oman, both small countries with highly idiosyncratic economic structures — achieved this without manufacturing-led development. Every other country on that list built its prosperity by expanding manufacturing capabilities.

More recent data by the UN Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO) arrive at similar conclusions. In their Industrial Development Report 2026, they highlight that 64% of growth episodes over the last 50 years can be directly attributed to manufacturing. Specific case-study evidence strengthens this hypothesis. The two most successful economic development stories of recent times as measured by sustained economic growth, China and Vietnam, achieved rapid growth through export-led industrialization. Both countries are currently two of the world’s strongest manufacturing economies (China, unquestionably, being the strongest).

In fact, the full historical record shows that no country except a few natural-resource rich states (mostly oil-dependent) or tiny financial havens has achieved high living standards without developing a competitive manufacturing sector. This is why “industrialized country” and “developed country” are used interchangeably.

The flip side tells the same story. Regions that have experienced premature de-industrialization have suffered growth slowdowns. Latin America, which went through severe de-industrialization in the 1980s and 1990s, saw manufacturing’s declining share of GDP coincide with decelerated growth. In Africa, premature de-industrialization caused negative economic growth in the same time period. Even OECD countries have experienced growth slowdowns alongside deindustrialization in the past few decades.

Manufacturing remains the engine of productivity growth and innovation

The new appeal of services is understandable, and we shouldn’t discount them. Many digital services do indeed provide some innovation and development. Megacities in India, such as Bangalore and Hyderabad, are prime examples. But when we examine what fundamentally drives productivity growth and innovation, manufacturing retains fundamental advantages that services struggle to match.

Manufacturing activities lend themselves more easily to mechanization and chemical processing. This, combined with the ease of spatially concentrating manufacturing production, enhances the potential of productivity growth through economies of scale — both static based on output level and dynamic through learning-by-doing effects. These advantages are difficult for services to replicate.

Additionally, studies using global input-output data find that manufacturing generates significantly higher productivity spillovers to other sectors than services do. Manufacturing also demonstrates stronger backward and forward linkages — purchasing inputs from and selling outputs to a wider range of sectors — which amplifies its impact on the broader economy.

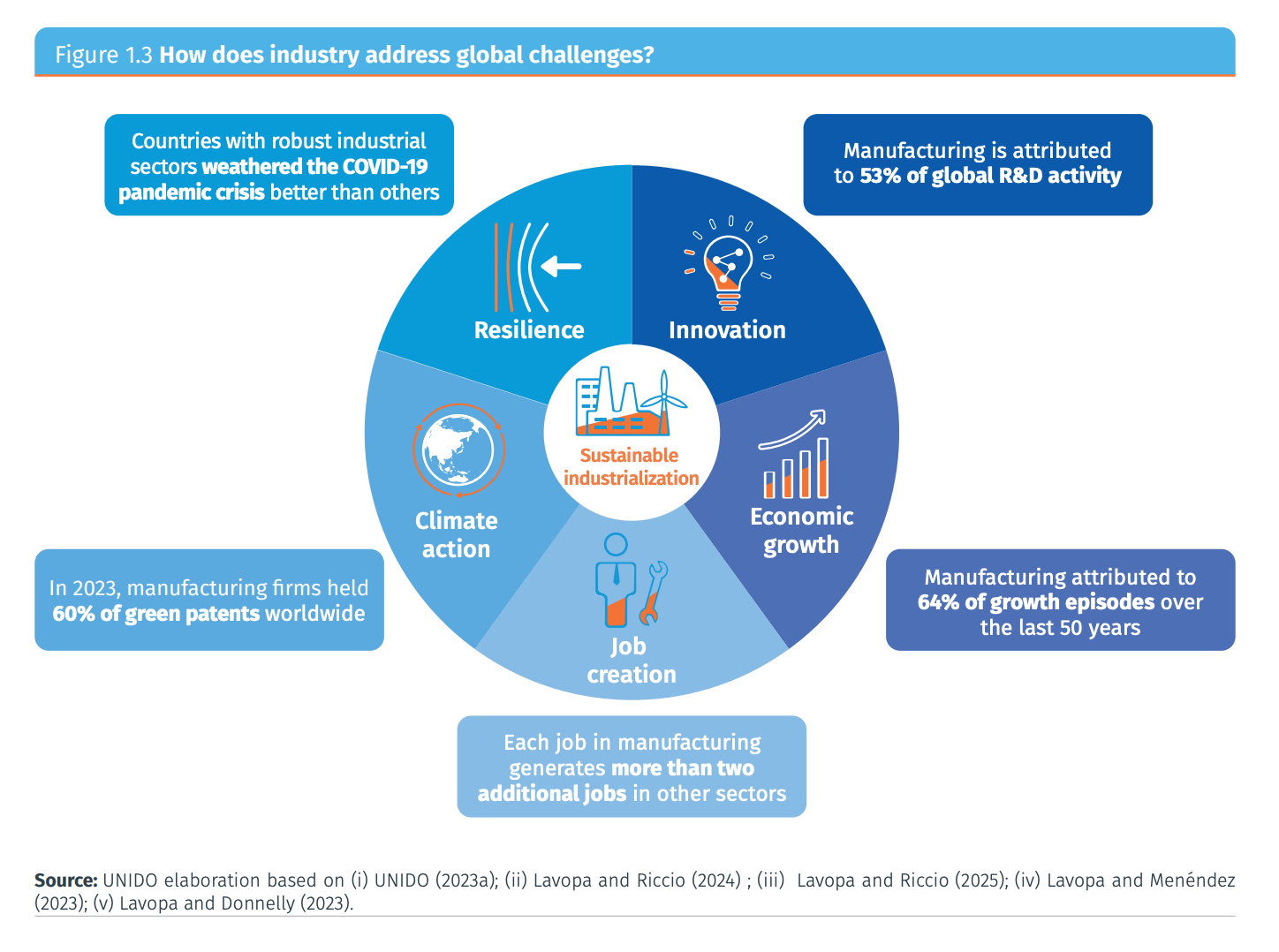

The innovation dimension is perhaps the most crucial one. Manufacturing firms spend heavily on research and development (R&D), generating strong innovation spillovers throughout the economy. In fact, manufacturing is attributed to 53% of global R&D activity. Manufacturing provides the material foundation for innovation, creates demand for new technologies, and enables the accumulation of productive capabilities that underpin further innovation. While some knowledge-intensive services like software development also drive innovation, the connection between manufacturing and technological progress runs deeper.

The evidence and arguments I’ve presented so far are captured quite well in the figure below — sourced from UNIDO’s Industrial Development Report 2026 — which shows how manufacturing is strongly connected to innovation, job creation, and economic development.

Manufacturing drives international trade

One reason the “services revolution” narrative has gained traction is that trade in services has expanded. Thanks to digitalization and the internet, many services can now be delivered remotely. India’s IT services, the UK’s financial services, and the growth of business process outsourcing all seem to validate services as a new engine of trade-led development.

But when we examine the evidence carefully, manufacturing remains dominant in international trade — and this matters enormously for economic development. Export of goods (dominated by manufactured goods) accounts for roughly 80% of all global exports. Exports allows countries to specialize, achieve scale, and become competitive, all of which accelerate productivity growth and technological development. Manufacturing has historically been far more tradable than services, and this advantage persists.

Manufacturing goods are inherently more storable, standardizable, and transportable than most services. Manufacturing also benefits more strongly from “learning by exporting”— firms competing in manufacturing are forced to innovate and improve productivity. A factory can produce for millions of global consumers; most services remain constrained by local demand. For developing countries trying to achieve rapid transformation, accessing global markets through manufacturing exports has proven indispensable.

Of course, some services that are tradable also enjoy these benefits. However, because a majority of services cannot be traded, the symbiosis between exports and industrialization are stronger. No one has yet found a way to remotely cut someone’s hair, clean someone’s house, serve someone’s food, build someone’s house, or mow someone’s lawn.

Automation is not the threat it’s made out to be

Perhaps the most common objection to manufacturing-led development today is that automation will eliminate the jobs that made industrialization so powerful for development in the past. If robots can perform the routine tasks that once employed millions in textile factories and assembly lines, won’t automation close off the manufacturing pathway for today’s developing countries?

This fear is understandable but overstated. Since the first Industrial Revolution, societies have witnessed continuous workforce disruptions from technological change. The Luddites in 1811 feared automation would destroy textile jobs — and for some artisans it did. But the broader industry saw employment growth because automation increased productivity, lowered prices, and created new jobs.

More recently, automation in manufacturing has generally not led to net job losses. A study of Spanish manufacturing firms from 1990 to 2016 found firms using robots generated employment because output gains outweighed labor intensity reductions. The UN Industrial Development Organization calculated that the growth in industrial robot stock had a positive effect on global employment from 2000 to 2014.

For developing countries, multiple barriers limit automation’s impact. Most automation technologies are developed for high-wage contexts and only become economically viable when labor costs are high. In labor-intensive industries like textiles and food processing, automation often cannot compete with low-cost labor. A report by the UN Conference for Trade and Development notes that “what is technically feasible is not always economically profitable.”

The most sophisticated forecast studies predict workforce reorganization rather than mass unemployment. McKinsey estimates that 3-14% of the global workforce will need to switch occupational categories by 2030 — consistent with historical workforce reorganizations, not an unprecedented crisis. Automation may transform manufacturing, but it won’t eliminate manufacturing’s role in economic development.

China’s labour-intensive industrialization in particular challenges the idea that automation inevitably displaces workers. Labour absorption in China’s manufacturing ecosystem has remained strong alongside the rapid adoption of industrial robots. China’s manufacturing ecosystem currently employs roughly 200 million workers — more than a quarter of the national workforce — demonstrating an exceptional capacity for labour absorption (estimates vary depending on how one defines the manufacturing ecosystem).

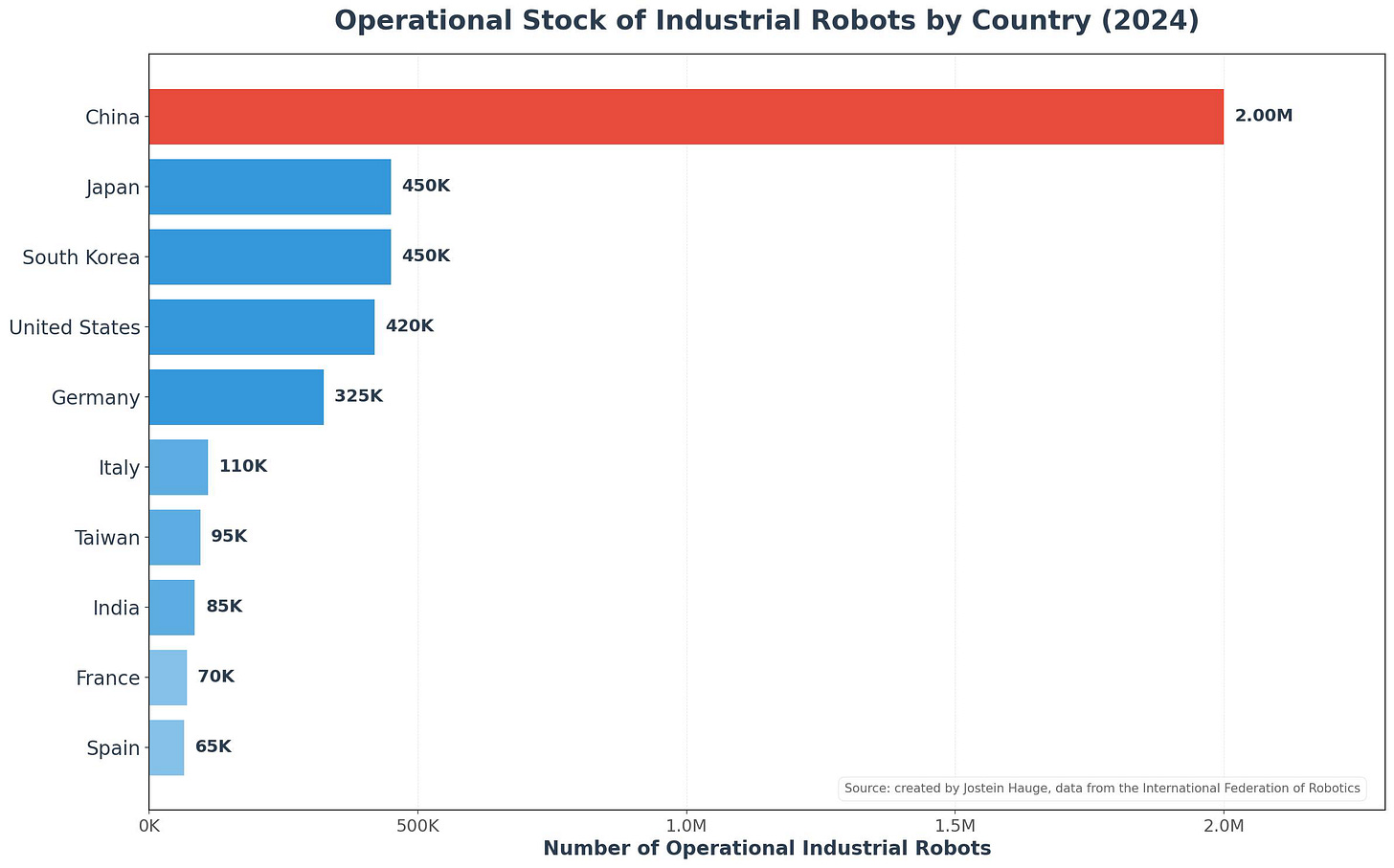

This strong labour retainment in manufacturing (China’s peak was reached in the early 2010s) has occurred in parallel with one of the highest growth rates of industrial robot adoption in the world. China’s installed stock of industrial robots grew ten-fold from 2014 to 2024 — from approximately 200,000 to 2,000,0000. China’s stock of industrial robots is currently the highest in the world, dwarfing all other countries.

While automation has undoubtedly displaced some workers within China’s manufacturing sector — and employment in China’s manufacturing ecosystem has slightly declined from its peak in the early 2010s — the overall evidence shows that large-scale labour absorption in manufacturing can coexist with, and even accompany, the diffusion of advanced industrial automation technologies.

Is China crowding out industrialization elsewhere?

China’s manufacturing dominance raises an obvious concern. If China’s share of global manufacturing, which now stands at 35%, keeps growing, doesn’t this necessarily crowd out industrialization opportunities for other developing countries?

The claim that China’s manufacturing dominance is preventing industrialization elsewhere overlooks a crucial fact: very few countries managed to industrialize successfully even before China’s manufacturing boom. Most countries that struggled to develop manufacturing capabilities in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s — long before China became the world’s factory — continue to struggle today. China didn’t create the barriers to industrialization that most developing countries face.

More tellingly, Vietnam, the country with the most impressive growth of manufactured exports per capita, is heavily integrated into China’s manufacturing ecosystem. Vietnam’s industrialization success contradicts the crowding-out hypothesis. Rather than being blocked by Chinese competition, Vietnam has leveraged its connections to Chinese supply chains, technology, and investment to rapidly build competitive manufacturing capabilities. This suggests that proximity to China’s industrial base can enable rather than prevent industrialization when countries pursue the right strategies.

China’s rise does present real challenges — simple math dictates that as one country captures more of the global manufacturing pie, less manufacturing occurs elsewhere. But when we see China partnering with developing countries to enable infrastructure development, energy sovereignty, and manufacturing opportunities, there’s clear evidence that China’s industrial ascent creates also create possibilities for structural transformation.

A recent book investigating China’s rise in Africa highlights that China provides real industrialization opportunities for the continent. It highlights two channels through which China contributes to industrialization in Africa: (a) infrastructure finance and construction, and (b) direct investment in manufacturing. The book, however, does emphasise that outcomes are uneven and highly dependent on national policy and agency. African governments, firms, and workers negotiate, contest, and shape these outcomes. In particular, the state’s ability to discipline capital and proactively steer industrial policy is crucial.

Making things still matters

Most successful development stories — from Britain’s Industrial Revolution to South Korea’s transformation to China’s ascent — have run through the factory floor. Manufacturing drives productivity through economies of scale that services struggle to replicate. It generates innovation spillovers that ripple through entire economies. It enables countries to access global markets at a scale services cannot match. And contrary to fears about automation eliminating manufacturing jobs, countries like China demonstrate that manufacturing can absorb hundreds of millions of workers even as robots proliferate.

Services are of course not unimportant. Digital platforms, financial services, and business process outsourcing create real opportunities for development. But they cannot replace manufacturing’s role as the engine of sustained productivity growth and structural transformation. Countries that have neglected industrialization — or lost it prematurely — have paid the price in terms of slower growth, persistent trade deficits, and diminished innovation capacity.

The factory of the future will look different from the factories of the past. But manufacturing — transforming raw materials into finished products — will remain central to development. The path to prosperity still runs through making things.

Strong piece. One way I’d frame it:

Manufacturing isn’t special because it’s “old economy.”

It’s special because it forces binding constraints.

Energy, logistics, quality standards, export discipline, scale, these can’t be simulated or selectively adopted. They compel coherence across the whole economy.

Many service-led growth stories look impressive, but remain non-binding, they scale until conditions change, then unwind.

That’s why countries don’t skip industrialization.

They can delay it, but they can’t bypass the phase where development is forced to become durable.

Yes! Another interesting angle… Industrialization rewires how societies think, organize, and behave. It reorganizes society. It forces the creation of management cadres, standardized procedures, accounting systems, time discipline, and operational hierarchies. In doing so, it instills a form of economic rationality — a culture of planning, measurement, and performance — that reshapes behavior far beyond the factory floor.